Critics of the pharmaceutical industry have long complained that drug companies resort to unscrupulous tactics to market their wares, handpicking friendly researchers (to whom they pay handsome consulting fees) for clinical trials, ghost-writing the results, and running studies for the express purpose of encouraging the adoption of new drugs. Such studies are known as "seeding" trials, and a new report in the current issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine reveals in disturbing detail how one company -- Merck -- paid for, ran and published such a seeding trial without bothering to tell the so-called authors of the study its true purpose: to encourage the use of Vioxx among primary care physicians. Indeed, as the editorial accompanying the report notes, "...deception is the key to a successful seeding trial. Institutional review boards, whose purpose is to protect humans who participate in research, would probably not likely approve an action that places patients in harms' way in order to influence physicians' prescribing habits."

As the Annals report notes, the seeding trial itself had little scientific merit. At the same time the it was launched, Merck was also starting the VIGOR trial to be the "definitive study of gastrointestinal toxicity." Interestingly enough, both the seeding trial, known as ADVANTAGE, and the VIGOR trial, uncovered the increased cardiac risk for Vioxx compared to naproxen, although as the world now knows, that risk was underestimated when the VIGOR study was first published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2000.

The true purpose of the ADVANTAGE trial only became apparent because the extensive litigation around Vioxx unearthed internal Merck documents that showed the extent to which its marketing department had planned and run the whole shebang. As this and other cases illustrate, it is very difficult to get an inside view of drug company tactics short of a subpoena or official law enforcement request. Indeed, it took both to pry out of GlaxoSmithKline internal documents that showed the extent to which the pharmaceutical giant had tried to suppress negative results about the safety and effectiveness of its blockbuster antidepressant, Paxil.

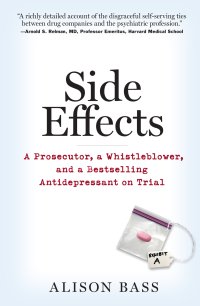

As I reveal in Side Effects: A Prosecutor, a Whistleblower and a Bestselling Antidepressant on Trial, GlaxoSmithKline only gave up these damaging corporate documents after an official request from the New York Attorney General's office and a subpoena from lawyers representing the families of teenagers who killed themselves on Paxil or tried to. The resulting New York AG lawsuit essentially forced GlaxoSmithKline to post the results of all its clinical trials, negative as well as positive, on a publicly available website and led to other reforms as well. Yet such valuable "windows" into the drug industry could be closed if the US Supreme Court allows federal agencies to "pre-empt" state lawsuits against the drug industry. That is something none of us should wish for.

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

Tuesday, August 12, 2008

A flawed system of drug research, or why new drugs often do more harm than good

The August doldrums have settled in. Pharmalot is on vacation, as are most state and federal legislators. But there's a few items I'd like to take note of, since I too was on vacation when this news broke:

1. Stanford University finally saw the light and removed its chief of psychiatry, Alan Schatzberg, as principal investigator of an NIH study after Sen. Chuck Grassley continued to question Schatzberg's alleged conflicts of interest in the study. As you may recall from my previous blogs, Schatzberg owned $6 million in stock in Corcept at the same time that he was principal investigator of a study examining the effectiveness of Corcept's drug, RU-486, in treating psychotic depression. Grassley, a ranking member of the Senate Finance Committee, charged that Schatzberg failed to fully disclose his financial interests in Corcept to Stanford or the NIH, which is funding the RU-486 study. As Stanford said in its statement to the Senate Finance Committee, "having Dr. Schatzberg as the principle investigator on this grant can create an appearance of conflict of interest." Here's the letter Stanford sent to the NIH notifying them of its long overdue action.

2. Research reported at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association echoes what I conclude in my book, Side Effects: A Prosecutor, a Whistleblower and a Bestselling Antidepressant on Trial: Americans are often exposed to unacceptable side effects because of flaws in the way new drugs are tested and marketed. Donald Light, a professor of comparative health policy at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, reported that two in every seven new drugs result in side effects serious enough for FDA action after the drugs have been approved, including black box warnings, adverse reaction warnings, or even withdrawal of the drug. Light also contended that drug makers design trials to minimize evidence of toxic side effects. For instance, they sample a healthier population of patients than those who will actually take the drug, excluding people who are older or have multiple health problems, according to GoozNews. Trials are also not run long enough to detect long-term side effects, Light says. In his talk, the sociologist noted that while current system of drug approval allows companies to boast that a drug is safe and effective, in reality, the label should read "apparently safe based on incomplete information..." Light concludes, as Side Effects does, that the FDA's sped-up drug reviews during the '90s and the first part of this century only led to significantly increased black box warnings and drug withdrawals after great harm was done.

1. Stanford University finally saw the light and removed its chief of psychiatry, Alan Schatzberg, as principal investigator of an NIH study after Sen. Chuck Grassley continued to question Schatzberg's alleged conflicts of interest in the study. As you may recall from my previous blogs, Schatzberg owned $6 million in stock in Corcept at the same time that he was principal investigator of a study examining the effectiveness of Corcept's drug, RU-486, in treating psychotic depression. Grassley, a ranking member of the Senate Finance Committee, charged that Schatzberg failed to fully disclose his financial interests in Corcept to Stanford or the NIH, which is funding the RU-486 study. As Stanford said in its statement to the Senate Finance Committee, "having Dr. Schatzberg as the principle investigator on this grant can create an appearance of conflict of interest." Here's the letter Stanford sent to the NIH notifying them of its long overdue action.

2. Research reported at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association echoes what I conclude in my book, Side Effects: A Prosecutor, a Whistleblower and a Bestselling Antidepressant on Trial: Americans are often exposed to unacceptable side effects because of flaws in the way new drugs are tested and marketed. Donald Light, a professor of comparative health policy at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, reported that two in every seven new drugs result in side effects serious enough for FDA action after the drugs have been approved, including black box warnings, adverse reaction warnings, or even withdrawal of the drug. Light also contended that drug makers design trials to minimize evidence of toxic side effects. For instance, they sample a healthier population of patients than those who will actually take the drug, excluding people who are older or have multiple health problems, according to GoozNews. Trials are also not run long enough to detect long-term side effects, Light says. In his talk, the sociologist noted that while current system of drug approval allows companies to boast that a drug is safe and effective, in reality, the label should read "apparently safe based on incomplete information..." Light concludes, as Side Effects does, that the FDA's sped-up drug reviews during the '90s and the first part of this century only led to significantly increased black box warnings and drug withdrawals after great harm was done.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)